We thank Báyò Akómoláfé for the permission to publish his essay ” What Climate Collapse Asks of Us”.

What Climate Collapse Asks of Us

Bayo Akomolafe, Ph.D. | The Emergence Network

This essay was first published on The Emergence Network’s ‘Mushroom Newsletter’.

Please visit www.emergencenetwork.org

In this (very) long essay, Bayo Akomolafe investigates the work and contributions of “postactivism” in our unique times by thinking about the nature of science and its products, climate change, the myriad organizations we invent to frame the phenomenon, and the bricolage of capacities and response-abilities that emerges from realizing that climate disruption is not a problem to be solved, but a barely-heard invitation to die well and fail creatively.

The greatest challenge the Anthropocene poses isn’t how the Department of Defense should plan for resource wars, whether we should put up sea walls to protect Manhattan, or when we should abandon Miami. It won’t be addressed by buying a Prius, turning off the air conditioning, or signing a treaty. The greatest challenge we face is a philosophical one: understanding that this civilization is already dead. The sooner we confront our situation and realize that there is nothing we can do to save ourselves, the sooner we can get down to the difficult task of adapting, with mortal humility, to our new reality.[1]

If something is being destroyed, is it perhaps forward movement itself?[2]

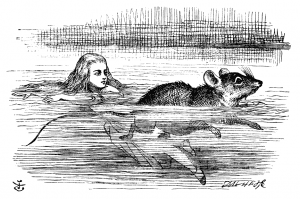

The photo hid everything.

When anxious bits of data from a global network of eight radio telescopes cohered into the first publicly accessible photo of a cosmic event from galaxy Messier 87, the media spoke about the scientific result in positively Galileoan tones. The “stunning achievement” and “unprecedented” precision of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) bestowed mankind with its first glimpse of a supermassive black hole, 55 million light years from Earth and 6.5 billion times the mass of our toddling sun. Six and a half billion suns compressed into a pin point. A devourer of worlds the size of a solar system. A titan lazily slurping lunch, his lips indecorously smudged with the remains of his prey: a lean diet of dust, gas, light, planet and stars.

Up till this exultant moment of disclosure, his appetite had been witnessed only by a mute expanse of oblivion stretching away from, but not quite escaping, the seduction of his hunger. Into his private vicinage stole 200 human scientists with a “camera”, peeling back the curtains that divide the mysterious from the ordinary. And out of it they came bearing the snapshot of a God. Cthulhu himself.

The photo itself hardly seemed threatening and barely intelligible: a ghostly halo of amber light wrapped unevenly around an innocuous splotch of shadow. A celestial glazed donut. The hung jejune jaw of Donald Trump. But the photo’s characterlessness was beside the point. We of the species that transported people to the moon, built the pyramids and sailed the seas, had finally made God in our own image. “We’ve exposed part of the universe that we thought were invisible to us before,” declared the bespectacled Sheperd Doeleman, director of the EHT project. “Nature has conspired to let us see something that we thought was invisible.” Listening to Doeleman, I couldn’t help but imagine the weightier significance of his words. The invisible tamed and rendered accessible to the will of machine-human conglomerations. A god humbled by creation. The eternal set to clock time. The returning messiah imprisoned in Seville. Dostoevsky vindicated.

A team from the EHT project shortly after approached Larry Kimura, a silver-haired professor from the University of Hawaii, Hilo.

Kimura, dubbed the grandfather of Hawaiian languages, used to eavesdrop on his own great aunts and uncles as they told stories from Hawaiian folklore. As a kid, he would sneak close enough (not too close to be shooed away) to hear the creation stories of the Great Sky Father Wakea, the Great Spirits born in Tahiti, and the kupua tricksters, his ears curdled with the rhythms and dance of his native tongue. In times-yet-to-come lurking in those innocent moments of awe, a future Kimura grows concerned that his language might go extinct, having just been reinstated as the language of the land after being banished by colonial regimes. He co-founds a non-profit called ‘Aha Pūnana Leo’ to create pre-schools that teach children the language. E Ola ka ‘Ōlelo Hawai’i (“the Hawaiian language shall live”), declares the motto of the school.

An even older Kimura listens calmly to the group from EHT as they ask him to christen the newly photographed black hole. No pressure. He would just have to listen closely. He rubs the image of the entity between his fingers. His young ears, still attuned to the animated stories and gossip of his aunts and uncles, perk up. From the thick of their conversations, a name calls out to him. He reels it in, through the brackish waters of memory and imagination: Powehi.

The nickname comes from a celebratory chant in honour of the Hawaiian creation event. Powehi. Embellished dark source of unending creation. An ironic title for a destructive force of epic magnitudes. Kimura knows something the EHT cohort doesn’t. They see a ravenous beast consuming galaxies unfortunately perched at its accretion disk; he sees life flourishing. They see a scientific product. He kowtows before the Unthinkable One. A Messiah. Herald of the Incalculable. The name Powehi, not yet approved by the International Astronomical Union, disturbs the stability of what is seen, and calls into question what is noticed or what is obvious. Destabilizing science’s claims of superior access to pristine Nature. The name is not a label, it is a gasp – the only appropriate response when one faces a god. The new name is adopted by the group nonetheless, marked into notes, cheered into life with a handshake. Much better than “Black Hole of Messier 87”. On the table in Kimura’s office, left alone as the diminutive professor escorts the nerds outside, the photo of Powehi murmurs with a billion restless voices hiding behind the pixels of human ingenuity. Ghosts that persist in many other places.

***

9000 miles to the east of Kimura and the two telescopes in Hawaii, a turtle pulls away from the summer-beaten Pacific and onto an island in the Maldives. She has not done this before, but she knows the drill. It is written into her reptilian bones, embroidered upon her membranes. A knowing closer than her breath. The way of her people. Her gravid body seeks a good spot to lay her eggs. The eggs must be expelled or else she risks a painful dystocic death. She comes to a place on the beach, the same place she erupted through her egg and crawled out from her burial – a hatchling among the clutch of her unhatched siblings. The first of the bale to come. It is the same place her mother blinked for the first time too. And her mother’s mother. Through sand and the inviting smell of the Pacific blue. She knows this beach. Except it isn’t a beach anymore. It is the middle of a new airport runway surfaced with tarmac. And that airport is a tentacle of a larger organism of airports, planes, satellites, machines, data, beeping sounds, laptops, skyscrapers, breaking news reports, neon lights, and stories about human triumph. The earth has changed. It is too late. She cannot hold them in any longer. She has travelled through time, too far, to hold them in her weakened body a second longer. One egg lands with an inhospitable thud on the gravelly grey. If you listened closely, a thunderous chorus of squeaks, clicks and chirps could be heard that day – the haunting ancestors of this turtle and the progeny in spontaneous mourning.

Bringing science down to earth

Science is popularly believed to be the story of unfiltered access to Nature as it really is, divorced from culture. Outside of opinions, beyond biases and preferences, resting at a prestigious remove from the tangle of subjectivity, is an objective world of Facts. A world of precise things and discoverable identities. A world of truth independent of value and politics, free-floating and pre-existing. The world 18th century English poet Alexander Pope extolled in his 1727 epitaph to the recently deceased Isaac Newton: “NATURE and Nature’s Laws lay hid in Night: God said, ‘Let Newton be!’ and all was light.”

According to this popular view of science, the world is still, a damsel in distress in passive wait for the appropriately powerful instruments to pierce through (in one phallic move) the veil that divides appearance from reality. Science is the appointed hero. Science may get the answers wrong time and again, but it is self-correcting – inexorably poised on the event horizon of certainty. In the clutch of cultural performances – superstitious stories of sky fathers and tricksters and magic – science is the lone hatchling, superior in ontology, exposed to the Real.

Presumably, most of us will never apprehend this real mathematical world of blinding light, stuck as we are in the compost heap of a lesser realm. Instead of generating facts, our social worlds are defined by the sweat of our experiences, half-baked ideas pretending to be fully-formed facts, gossip, cultural conditioning, outrageous doctrines and funky faith. The secondary world of appearances. Unlike Newton and his colleagues with VIP passes to the Holy of Holies, able to decipher the cryptic whispers of Nature, the elegant code that connects a bovine galaxy in swirl yonder to the quantum intricacies of an atom here, we may never know things as they really are. We would not even know of this Newtonian world were it not for the scientific method, the curious rituals through which the scientific priestly caste alchemize drops of truth from the base elements of the familiar.

So, for many casual consumers of the news about Powehi, the black hole was merely yet another “discovery”. A remarkable one, but not too shocking given our scientific history of achievements. It’s par for the course. A trophy alongside the telescope, quantum computing, and the black body in its once three-fifths-ness. The image that was printed on the pages of the dailies, the same one that lit up on smartphones and computer screens everywhere, was a true representation of a black hole. The name Powehi was cute at best, but the world it came from – the one Kimura knew, the world of spirits and monsters and tricksters – was secondary to the one the EHT scientists knew.

In a virtual conversation with someone about climate change, and in an attempt to hail alternative ontologies, I uttered the words that have haunted me ever since I started to pay attention to African philosophies: “The times are urgent, let us slow down.” He retorted crisply, acknowledging the place of indigenous customs and sayings. “But this is a global matter. And the science supports it.” What I heard was the silent implication that while it might be politically appropriate to pay lip-service to multicultural perspectives and insights into contemporary challenges, ‘science’ is a superior, more-than-cultural, value-free practice. Ahistorical, neutral, stoic, and foundational. And its adjudications are in principle uncontroversial glimpses into the heart of things where culture could only flail and wax poetic in its eternal inadequacy.

This is a ubiquitous view: that the rituals of scientific knowledge-making are one ontological decibel above other forms of knowing, inherently privileged with truth. We are used to thinking of the world as a settled matter, science as the practice that seeks to form opinions and ideas about this world, and truth as correspondence between our ideas and the world as it is. We think that indigenous concepts, theological and political gestures require scientific validation to be real. That there is a stable reality ‘out there’, an end that does not vary even when the means do. That perspectives and thoughts are primarily matters of human subjects.

Thankfully, with science and technology studies (STS)[3], the culture of science is being taken seriously. Turns out, science is just as contingent and performative a way of knowing as casting cowries with Ifá to divine a way forward. And the pretensions of technoscientific practices to purity have long been questioned and dismantled by abler essays. By ‘performative’, I mean to stress how ‘objective truth’, supposedly independent of observational methods and universally accessible regardless of context and means, is actually already frontloaded with biases, ideologies, expectations, cultural materialities, textures, and algorithms. I mean to conjure a world that is not at all composed of ‘things’, already possessing properties and features (weight, mass, capacity, etc.), but a maelstrom of relationships in open-ended becomings.

Let’s make sense of this.

Unbeknownst to many, there is a legacy of ‘distance’ at work here – a legacy that cuts the world into neat binaries and puts a wide gulf between objects: words versus things, subject versus object, here versus there, mind versus matter, culture versus nature. Appearance versus reality. A legacy that is suspicious of mere appearances, and seeks to read the hidden code behind everything. This vision of the world thinks of it as a mechanical container of gears, nuts and bolts – things that have determinate measures and inherent values unique to them.

On the continent of Europe, an evolving set of philosophical ideas about the nature of nature developed during the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods, producing this legacy of separation. Sedimenting over centuries, powered by anti-monarchical sentiments that crystallized in the French Revolution of the late 1700s, a rationalistic vision of the world took hold of public imagination. Gone were the superintending regimes of Gods and angels. Now was the time of Man and his Age of Reason, powered by Facts, driving on the rough but surmountable terrain of progress and advancement. Empiricism and reductionism became science’s modus operandi in modifying the new world now liberated from enchantment. This triumphant vocation opened the way to the Industrial Revolution.

Ironically, from within the very heart of science’s world-altering work, a series of unanticipated challenges have arisen. In biology and the physical sciences, sharper instruments have blurred the presumed boundaries between humans and their earthly cousins: concepts like Lynn Margulis’s ‘holobiont’ recast humans as companion species, intra-dependent with bacteria and microbial life, instead of fundamentally superior beings; in quantum physics, especially the Copenhagen interpretation of a much more dramatic and scandal-ridden world than most Enlightenment philosophers could dream of, ‘facts’ are not ‘facts’. There aren’t independent objects or things floating around in the world awaiting the vision of scientific observation. In fact, there aren’t ‘things’ at all; things are the temporary identities we fasten upon fluid relationships in order to navigate the world conveniently.[4]

I have written the words – “facts are not facts” – painfully aware of how that might be interpreted in a troubled time when “fake news”, proto-fascist sentiments and a postmodern dismissiveness of accountability defines political relations. In a time of urgency when this dismissiveness is being weaponized to fund the destruction of our environments. To acknowledge the duplicity at the heart of the scientific enterprise and its production of facts is however to bring science down to earth and situate it within an entangling and messy world.

Authorand researcher of Roman archaeology Astrid Van Oyen writes that “…ethnographers of science have muddied the supposed purity of the modernist scheme itself by showing how scientific facts – the epitome of western immaterial rationality and its Enlightenment principles – rather than deriving from purely abstract eternal laws, are contingent upon such things as the size of test tubes, the distribution of funding, and the focus of gossip. This is not to say that science is untrue or unfalsifiable; it is rather to specify that its validity is built on foundations of a different nature and reach than previously imagined”[5]. This ‘different nature’ Van Oyen writes about is a vision of a world where nature spills corrosively through its categories and touches culture (and vice versa), and one in which humans do not possess any characteristic exteriority that might grant them a ‘God’s eye point of view’ on things. A world where humans are not central to meaning and value, but part of a field – an always emerging flowing that enlists humans and nonhumans alike in a rhapsody of possibility.

Van Oyen and contemporary researchers into the material culture of science are pointing out that we have to think of facts differently. Whether those facts are climate change, black holes or gravid turtles. These are not sterile objects that merely take on the inscriptions we assign to them, and they are not permanent furniture in a static universe. If – as some interpretations of the weird and wacky world of quantum physics tell us – the act of observing a wave in a double-slit experiment alters its identity, then the observation is inescapably a part of the very identity of the wave or the particle that materializes as a result of that observation. Scientists had once presumed that the closer they looked, the more information they could excavate from the object of their observations. Now it seems to be the case that making observations is not passive and innocent work, but actually alters the ‘thing’ being observed. The subject-object dichotomy breaks down. As such, the ‘things’ that science offers up for our consideration are not things at all: they are relationships. The black hole phenomenon called Powehi is not just an observation-independent spectacle in outer space, discoverable and rendered visible by dint of hard work and resourcefulness; it is the entity in space, the human actors, the satellites of the EHT, the hard disks and notepads strewn across office desks, the culture of human exceptionalism, the language conventions and gender-based politics of representation activated in similar bureaucracies, government funding, lack of government funding, nation-states, private agendas, colonial erasures, and – yes – a turtle struggling to give birth.

We do not usually rope things together this way – and that’s because modernity teaches[6] us to see only isolated and reductionistic ‘objects’, instead of contingent, fluid, emerging frameworks and relationships.[7]

As is usually the case with invisibilized knowledges lying in the shadows of colonial sciences, the Yoruba people of West Africa[8] – just one among many non-western peoples – have taught this entanglement for a long time. Long before quantum experiments started to show that the emperor had no clothes on after all. The Yoruba have always understood that everything is a crossroads – not just an intersection of other things but relationships resisting absolute determinacy. Things are assemblages. Provisional, multitudinous, spread out. Like rhizomes.

***

Thinking of how science creates its knowledges is important to thinking carefully about climate change and what it asks of us. There are generally two conceptions on how everything comes to be: one is an arboreal model that resembles a tree with its roots and trunk and branches and leaves. There is a foundational and classificatory sentiment here that figures how ‘things’ flow in a unidirectional causal pattern – from roots to tips of leaves. What this model assumes is that things are discrete and follow each other in some Newtonian cascading fashion. In more recent years noticing the porosity of things, of categories, has opened up new ways of understanding the world. This second conception of how differences emerge, how things materialize, deploys the idea of the rhizome to express the stunning interconnectedness that characterizes everything.

French philosophers Felix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze employed the botanical figure of the rhizome to illustrate the striking interconnectedness and relationality of the universe:

In Deleuze and Guattari’s work “rhizome” is roughly the philosophical counterpart of the botanical term, suggesting that many things in the world — to be consistent, if one follows the direction of their thinking, “all things” in the world — are rhizomes, or rhizomatically interconnected, although such connections are not always (in fact, seldom) visible. Animals or insects that live symbiotically appear to be an obvious example, such as the little birds that clean crocodiles’ teeth when these reptiles bask in the sun with their huge jaws open: instead of eating the birds, the crocodiles let them feed on the bits of meat, etc, between their teeth — their teeth are cleaned, and the birds are fed, in this way forming a rhizome. After all, when one sees them separately, few people would guess that their species-economy is rhizomatically conjoined.[9]

A single blade of grass. A single laptop computer. A livid and gaseous bottle of Coke. A single leather-bound notebook. A single plastic cup. A single image of a black hole 55 million light years away. A single scientific fact. None of these are at all singular or settled. Every morsel of the real is a framework, a rhizome, a trace. Every point a patchwork of crosshatchings of intersecting shimmering worlds too heavy for our persistent paradigms of intelligibility to articulate. Powehi, like other photographic products, is not the representation of an outside universe. Pictures after all aren’t taken, they are made. A conspiracy of the manifold. A performance. A chorus of the many.

The figure of the rhizome invites us to see that we are inextricably part of nature, performing the world, contributing to its emergence – just in the way we are also modified by the world in and around us. There is no culture apart from nature, and no nature that can be cut away from culture.[10] To know the world is not to sit outside of it and reflect upon it in order to gain clarity (a representationalist position). How we move through the world, where we stand or sit, the instigations of the ground beneath our feet, the migrations of clouds, and everything else between are all threads that stitch a tapestry of knowing that can only be for the time being.

Perhaps the most unsettling implication of the rhizome for those committed to a view of the scientific enterprise as an illuminating endeavour is that “facts” – as we must now come to see them – are simultaneously acts of concealment and disclosure. What is revealed, what we learn to see, what we pay attention to, what is permitted intelligibility always comes subsidized by aspects of an entangling web of relations that are erased from mattering. The invisible always underwrites the visible. It is the asymmetrical/complementary dynamic between the ‘two’ that worlds the world.

In the case of Powehi, the turtle.

And in the case of urgent reports about climate change and the rush to solutions, an old complex of ideas that sprang to life somewhere during the Holocene, at the end of the Ice Age when the ice began to thaw, and when the relative stability of the world around us instigated us to build cities and eventually capitalist settlements and see ourselves as permanent fixtures instead of transient bodies.

Climate change: how we see the problem is part of the problem

Riel Miller walked down an invisible street in Paris. Invisible because I couldn’t see it. Through my phone I could hear the beeping, the amorphous cacophony of a restless traffic of a city in the simmering heat of righteous revolt, the conspiratorial gossip of passing winds in the open, and the laboured breathing of my friend.

Riel works with an intergovernmental organization I will not name, and has been powerfully instrumental in the creation of a methodology that queers the conventional rituals of forecasting trends and predicting future scenarios (“trying to colonize the future” he says), situating these cognitive gestures within a complex and complicated world that does not necessarily abide faithful to our analyses. Calling his visionary approach ‘Futures Literacy’, Riel has been on a mission to demonstrate the materiality of thinking and the urgings of ghosts that lurk behind our ‘anticipatory assumptions’. I have often imagined Riel as a “Jor-El” kind of figure – the biological father of Superman, and chief scientist on Krypton whose final task on an imperilled planet – just after excoriating that world’s leaders for failing to heed his warnings about doom – is to build a rocket ship sanctuary for his son and then blast him off in the direction of a little blue planet in a different solar system. Riel, like Jor-El, trafficks in dangerous ideas and has outrageous coordinates. Once an improv dancer, presently an avid cook and jazz enthusiast with a masterful on-one’s-fingertips appreciation of wines and their oenology, Riel has an abnormal mission in a system of humanistic and humanitarian agencies designed to emphasize the problem-solving capacities of our ‘species’: to show that we won’t out-think our way out of our problems. Thought, he would argue, is not something we do well. Further still, thought is not as unequivocal, human and disinterested as we might suspect. Consequence of this ghastly footnote to human supremacy? How we define our problems is part of the problem, and we will often repeat and reinforce those problems in the name of enacting resolutions.

Riel and I were talking about COP25, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC) happening in Santiago, Chile in the latter part of 2019. I asked him a question. What’s the word on the street? In the ongoing struggle with untoward weathering patterns, and especially in light of new thresholds and timelines like ‘2030’ or ‘2050’ (the former being the date for a slide into climate chaos, and the latter being the date for the ‘end of human civilization’[11]), what do climate activists and policymakers think about the state of things today? Riel told me that there was a greater appreciation for complexity. That many actors were coming to see that the challenge of ‘climate disruption’ stretched their frameworks and strategies of organization. I think they can make sense of an entangling world now, he said, still wading through the chalice of unsure opulence the city of Paris had become. They just don’t know what to do with that.

Who can blame them?

In the latter months of 2018, with the publication of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report on the status of global warming, a dreadful strain of impending doom once underwhelming and easier to dismiss gained amplification, quickly becoming an unending series of phrases about the massive amount of ecological damage wrought by human activity. A tome of catastrophe.

Depending on where you live, when you look out your window, everything might seem just fine. The sky is bluer than ever. The sun looks just alright. Birds and butterflies are still aflutter. People saying hello here and there. The internet still works. An ad runs on television showing a smiling model reassuringly inviting you to install a new bathroom. An ad later, a known celebrity guarantees that the insurance organization he represents knows a thing or two because they’ve seen a thing or two. Barring the occasional interruption of this steady stream of the familiar, it’s a fine day, another banal addition to the endless continuum of moments in empty time.

The story that climate scientists tell however bursts this bubble of the normal.

In 2015, with pomp and flair, all countries of the world (save two) entered into an agreement in Paris. The deal? Keep the increase in global average temperatures below 2C. The 31-page deal was to shock the world and its assemblage of nation-states off its current trajectory towards a 3.3C increase in global temperature since preindustrial levels. Most hailed the Paris Agreement as a milestone event, signalling the growing political will to counter the effects of climate change. 3 years later, the IPCC report, compiled by 133 authors, drawing from over 6000 peer-reviewed research papers, warned that keeping global temperatures from rising 2C was not enough. Issuing a tougher target of 1.5C, the report’s authors warned that we have 12 years (now 11) to drastically reduce emissions, reduce coal consumption and dependence on fossil fuels, reset our collective priorities, and remake society – or risk experiencing slippery effects that could turn the world on its head.

Picture swelling sea levels leading to coastal flooding and the migratory nightmares, poverty and death that will ensue as a result. Picture having to explain to your grandchildren what crabs were because they have no clue what the crustaceans look like, except through books. Picture having to stand with your family on the streets in line formations guarded by armed soldiers to receive limited inoculation from a new pathogen regenerated from thawing coastal permafrost.

An outlandish scenario? As the planet heats up, and ancient ice liquefies, scientists are reporting the release of ‘giant viruses’ with more genes than is common today among known viruses – diseases frozen for tens of thousands of years that we have little or no skills to counter.[12] That’s not all at stake. Along with marauding viruses from hell, even if we are able to keep global temperatures under a 1.5C rise, almost 14% of the planet will be exposed to extreme heat once every five years; the decline in coral reefs climbs to about 90% and the global annual catch of marine fisheries declines by 1.5 million tonnes.[13]The consequences of a 2C scenario – just half a degree away – are less conscionable. In both cases, as a number of reports are showing, the implications of warming affect food security, health, and the environment.

One report – authorized by the Australian Senate in 2017[14] – adds petrol to the stinging fumes, blasting away the curt conservativism of the IPCC model and predicting that without radical mitigation efforts in the next decade, human civilization could end by 2050. Arguing that the IPCC’s scenario-building apparatus was too reticent in its appreciation of the sheer complexity of Earth’s interconnected geological and political processes, the Australian document unfolds a narrative that reads like the plot of a filmic exploration into the origins of a dystopian, post-apocalyptic ‘society’:

What might an accurate worst-case picture of the planet’s climate-addled future actually look like, then? The authors provide one particularly grim scenario that begins with world governments “politely ignoring” the advice of scientists and the will of the public to decarbonize the economy (finding alternative energy sources), resulting in a global temperature increase 5.4 F (3 C) by the year 2050. At this point, the world’s ice sheets vanish; brutal droughts kill many of the trees in the Amazon rainforest (removing one of the world’s largest carbon offsets); and the planet plunges into a feedback loop of ever-hotter, ever-deadlier conditions.

“Thirty-five percent of the global land area, and 55 percent of the global population, are subject to more than 20 days a year of lethal heat conditions, beyond the threshold of human survivability,” the authors hypothesized.

Meanwhile, droughts, floods and wildfires regularly ravage the land. Nearly one-third of the world’s land surface turns to desert. Entire ecosystems collapse, beginning with the planet’s coral reefs, the rainforest and the Arctic ice sheets. The world’s tropics are hit hardest by these new climate extremes, destroying the region’s agriculture and turning more than 1 billion people into refugees.

This mass movement of refugees — coupled with shrinking coastlines and severe drops in food and water availability — begin to stress the fabric of the world’s largest nations, including the United States. Armed conflicts over resources, perhaps culminating in nuclear war, are likely.

The result, according to the new paper, is “outright chaos” and perhaps “the end of human global civilization as we know it.”[15]

Describing the phenomenon as an existential risk that will unleash the perfect storm of effects guaranteed to snuff out ordered human settlements, the report advocates “dramatic action…if the ‘hothouse Earth’ scenario is to be avoided”, championing a zero-emissions industrial system that gradually restores the climate to pre-industrial levels.

Buried within the reports however, behind stentorian headlines and ‘action points’, is a less articulate bewilderment about how to steer the anfractuous world-building machine of global industrialization away from the cliffs.

There are two general strategies of response to climate change: mitigation and adaptation. In the case of the former, which involves reducing or stabilizing the levels of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere[16] with climate engineering tactics like carbon dioxide removal (CDR), methane digesters and BECCS (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage), there are seemingly insurmountable spill-over ethical issues and hidden costs. For instance, with BECCS, converting vast swaths of land into monocultures of trees and crops that can extract carbon from the atmosphere is likely to exacerbate conflicts over land and water, drive up food prices, and destroy ecosystems and reduce biodiversity.[17]

Adaptation solutions are no less controversial.

Retrofitting existing buildings with solar panels or replacing ICE vehicles (internal combustion engines) with electric cars to ramp up our transition to renewable and sustainable energy sources might seem like a fairly straightforward and radical thing to do. In fact, like every rhizome, this set of responses is not straightforward at all. It is not radical either.[18] For one, it would take a lot of energy, mining and carbon proliferation to produce these cars and technologies, and – in the case of the cars – keep them charged and running.

It’s like a damned if you do and damned if you don’t situation. Most of what we can do[19] to save the day and reduce carbon emissions require us to continue doing what we’ve done before – the processes that lend themselves to global warming, if the greenhouse gas theory is to be taken for granted. Put simply, there are not enough resources to save the world. To do that, we’d need to destroy it.

Perhaps, if you are already sensitive to rhizomatic entanglements, then you might notice that the reason we are seemingly caught in a deadly and sticky cycle of toxic reinforcement, where redemption is the breakthrough we seek, is because this is what the ‘larger’ framework is doing. Here, another disturbing implication of a rhizomatic reality becomes clear: we never act unilaterally, we act in assemblages. We act together-with. We become-with. We think-with. We do-with. There is no doing that is not a doing-with. In a very pressing sense, agency (or the power to act) is not a human or individual attribute; it is an emergent quality of assemblages. When we suppose that all we need do in response to climate change is to come up with a technofix, the next bright idea, an ‘indigenous’ protocol, a policy statement or a piece of legislation, it is wise to notice – where this is possible – the ‘other’, often invisible, nevertheless moving ‘pieces’ (human, nonhuman, conceptual, material, etc.) that impinge on (or intra-act with) our efforts, and thus produce effects that stretch beyond ‘original’ intentions. In this scenario, we are not detached or separable human actors facing a discrete threat yonder; we are capitalist-political-ecological-spiritual-gastronomical-bacterial rhizomes intra-acting with the world. It is as I said while speaking in Kigali, Rwanda, at an innovation conference to a glamorous hall full of young people who had been told earlier to “think outside the box”: “Thinking out of the box is exactly how the box thinks. We are the boxes we strive to out-think.”

Thinking about frameworks helps us situate where power lies, helps us understand the ghosts that need to be appeased. In the Yoruba world, when a client presents herself before a babaláwo or medicine man, his skills as a healer are appraised by the community not by the precision of his diagnostic tools but by his ability to investigate the insurgency of the invisible, the hidden influences, the erased bodies and ghosts that keep good fortune away from the seeker – a strange meshwork of indiscernible claimants the Yoruba call “ayé”.[20] The next round of activities that the medicine man might initiate would be to invite the seeker to perform rituals or produce objects that on the face of it have absolutely nothing to do with reported problem. What has dipping oneself seven times in a river to do with financial fortune? What has plucking one’s eyelashes and stirring a single strand into one’s breakfast to do with curing infertility? In a Newtonian arboreal world where effect neatly follows cause, nothing. But in a rhizomatic world, where cause and effect dynamics have to be thrown aside in favour of orgasmic intra-actions that are mutually co-constitutive, the inappropriate thing to do might be the very thing one needs to do.

***

Far from being an objective ‘truth’, the supposedly hard-nosed end of a rigorous climate science research trajectory that tells us that carbon dioxide is the bogeyman to exorcise, is thus a framework of interested and largely invisible aspects of the world. It is not merely a neutral announcement about the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and the imperatives of reducing carbon emissions; it is a statement about who can do this, why we need to do this, and how we need to do this. Climate change scientific ‘products’ form an assemblage made up of party politics, privilege, bureaucracies that centralize human agency, the rationalization of the world and its reconfiguration as background to the lordship of our species, and ideologies that prop up international relations and nation-states as principal actors.

Actually, there have been many frameworks of the climate change phenomenon and many organizational systems that have struggled to carve out clarity about this phenomenon. These strategic gestures produce different kinds of capacities, enable response-abilities and disable others, and texture manoeuvrability. Campbell, McHugh, and Ennis write about climate frameworks in general:

Research in climate change has long been about the construction and interpretation of the object in question, and the output reveals highly diverse responses from individuals, organizations and societies… Frames are ‘general organizing devices’ that do numerous things: they define problems, diagnose causes and suggest solutions. They influence organizations by their argumentative strength and can determine the size of climate change, in the sense that they define and therefore produce climate change through the work of problem-identification, claims-making, attribution-laying, boundary delineation, counter-framing, bridging, amplification and constructing identity-forming vocabularies and discourses. Framing climate change in particular ways can alter an audience’s ideological beliefs and value sets about it.[21]

Noting that “the framing of climate change is not a static process, but evolves and regresses over time, as specific economic, social and policy contexts shift”, the trio in their paper go on to conduct a meta-survey of literature on climate change frameworks, eventually identifying as many as twelve distinct frames that have shaped enactments and understandings of climate change and climate justice from the late 60s and early 70s.[22]

When climate change was framed as an “Externality” in the 70s, the nature of the problem was believed to be a “malfunction in the market mechanism” occasioned by “uncompensated environmental costs of production and consumption.” Originating from economics, this evaluation led to the organizational response of trying to integrate those externalities, attempting to build a circular economy by emphasizing the benefits of ecological modernism.

An alternative but contemporary framework, dubbed the “wicked problem” framework, noticed that there was “no single or optimal solution”: solutions had a way of reinforcing the problems. Just action was sensitive to the political nature of solutions, dismissing the idea that a technocratic, politically neutral approach could engage with the ‘event’.

In 1988, the framework of “global warming” (as a result of the build-up of GHGs or greenhouse gases), shifted our focus to carbon, fossil fuels, temperature, human beings, and nature. De-carbonization, lowering emissions, appealing to the fear of externalities, and advocating for policy development with targets became the organizational response.

Other frameworks – including “Contested Debate” (which is argument-centred and which calls into question the validity of scientific research about climate disruption), “War”, “Risk”, “Crisis”, “Tragedy of the Commons” and “Anthropocene” – have given birth to different organizational configurations, each stressing a theme, the nature of the ‘bad guy’, the nature of the ‘hero’, and what ‘justice’ might look like.

The ‘Green New Deal’ – a recently proposed piece of legislation introduced by American Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – seems to be in part an exemplification of climate change as a “Super Wicked Problem”, yet another framework that has grown in prominence from 2007 upwards. This framework stresses the inadequacy of time to deal with the challenge; notices that those who cause the problem are endeavouring to solve it; and, berates the central authorities for being weak. The solution? “Incentivize organizations. Create path-dependent organizational interventions.”[23]

For Campbell, McHugh, and Ennis, none of these frameworks can ‘adequately’ calculate the algorithm of approaching climate change. Something different is required.

The current frameworks stretch and yawn, gasp and pant, choke and ache to name and localize a phenomenon that resists our taming. From a Deleuzian perspective, the frameworks or assemblages ‘we’ form are continually “deterritorialized” or broken through and disassembled by ‘things’ that show up as a result of the measurements we are making. It is like noticing wave patterns produced by single photons in a double slit experiment, and seeking to determine which slit each photon of light passes through – only to find to one’s dismay that instead of producing an interference pattern, the apparatus now produces a scatter pattern.[24] The very nature of the climate change phenomenon is not fixed – and different frameworks will produce different phenomena. Campbell, McHugh, and Ennis argue, however, that though it may seem as if we have historically had an abundance of frameworks to deal with climate change, all of them have been undergirded by a shared constant, a blind spot: us.

Informed by the organizational research of another group, they point out “how the threat of climate change is absorbed by organizations through a dialectical process of critique and reassessment,” or how orthodox organizational configurations serve only to distil the enormity of an “extinction-level event”:

Specifically, [Wright and Nyberg] chart how corporate organizations engage in framing work, interpreting and translating climate change into a strategic agenda, in order to overcome the tension between profit and ecological preservation. Gradually, the revolutionary import of climate change is framed as an opportunity, allowing the organization to create a consonance between these two opposing aims. As new criticisms of the organization surface, the organization engages in localizing and normalizing practices that cause the problem to splinter and be measured parochially. This results in the purification, dilution and dissipation of an extinction-level event. Ultimately, their model demonstrates how climate change is always conceived as something ‘outside’ that needs to be internalized by the organization. We extend their conclusion by adding that all organizations begin this framing act with the default notion of the outsideness of climate change. Climate change comes as a challenge, albeit grand, that must be internalized (to varying extents) by the organization.[25]

Campbell, McHugh, and Ennis finally insist that the reason we cannot solve the problem of climate change is because climate change is not a problem. We cannot save the world from climate change because climate change is the world – incalculably more complex and more multidimensional than our organizations can frame or address. “Climate change is so thoroughly unbounded that organizations exist within it, because nothing will exist outside it.” We struggle with it because of the dynamics of centralizing human permanence and survivability. We struggle because of a modernity-reinforced ‘feeling’ of entitlement that the world ought to be stable, convenient, and user-friendly. The post-Holocene turbulence we experience is existentially jarring: the message we cannot face is that we too are transient, that we are not the fulcrum upon which the universe is balanced, and that the coddling and pampering of a historical inflection in the natural rhythm of things must now give way to foreclosure.

The end of hope as we know it

I find this idea intriguing: that climate change is not a problem organizations can draw lines around, encompass or own. That it is ontologically unframeable, unthinkable and incalculable. These attributes do not belong to determinations of size and scale; they are not rhetorical strategies or hyperbolic attempts to stress how daunting the referent is. Instead, they signal a “break in referentiality”[26] – a coming to a place where appellations are not only useless, they are counterproductive. A coming to a ‘place’ of an elderly silence so compelling that one yields oneself to its operations, longing to be defeated. A place of creative surrender. The end of thought.

In what way is climate change unthinkable and incalculable? If climate change is more than just a problem, more than a threat, more than a crisis, more than a war, then what is ‘it’?

What are we being slowly invited to consider?

Campbell, McHugh, and Ennis conduct their analysis of climate change within a relatively recent philosophical tradition that situates a real and material world outside of human experiences of it.[27]Their desire is to ontologize climate change – that is, to give it real footing in the world at large, instead of situating it as merely a phenomenon of human attempts to know about the world (epistemology).[28]They then adopt Quentin Meillassoux’s concept of ‘advents’ to characterize the unprecedentedness of the climate change phenomenon. For Meillassoux, ‘advents’ are forms of “emergence without precedent” or specific points in the history of the universe when the laws of nature themselves have changed. This change is not brought about by a tinkering Hand, by an absolutely transcendent force outside of nature: it is written into nature’s radical openness. Nature’s utter creativity.[29] Meillassoux identifies three Worlds that have emerged from these advents: the World of the material, the World of life, and the World of thought. The World of the physical and the ‘world’ before that (if one could conceive of such a world) are so irreparably different, so rapturously unaffiliated, that one might think of the shift as fundamental. These radical discontinuities – the moment when matter emerged; the moment when life (“which”, in Meillassoux’s imagination, “cannot be reduced to material processes”) sprang forth; and the moment when thought or the capacity to arrive at intelligible meaning became possible – render “unrecognizable everything that has come before.” These advents are not reducible, justified or explainable by anything present in the familiar. They are traversals. Crossings. Altering reality in their flashing up.

Campbell, McHugh, and Ennis argue that we are – in a Meillassouxian sense – in a fourth World, conjured by a fourth advent. This advent/World of climate collapse exceeds thinkability, where thinkability and various forms of organization that gesture towards the world as an “other” or a “challenge” or “obstacle” to human progress are the furniture of a ‘previous’ world. The World that mothered the Holocene 11,700 years ago, the timescale of polite weather and less turbulence that afforded us opportunities to create “epistemological categories that lasted thousands of years and became the most fundamental modes through which we understand and organize – the births of language and religion, the concept of resources and exchange, the invention of all known technology, the development of agriculture, domestication and urbanization.”[30]

Contrasting the Holocene with what many now consider to be the post-Holocene world of the Anthropocene – the world largely terraformed by human activity – Campbell, McHugh and Ennis observe that it is the rift between these spacetimeframes that is of interest to them.[31] This is the ‘point’, through this crack, the unthinkable entered, so to speak. This is the sense in which “climate change outpaces organizing”.[32] An advent marks a quantum leap, a shock to the solution that freezes it.[33] The end of hope as we know it.

Selah: ‘enter’ the messianic

Everything thus becomes strange.

Something inarticulable, a twirling murmuration of a monster too wild to be tamed, too wild for form, too wild to be categorized and speciated, now sits in theophanic magnificence at the city gates. Like an elder cosmic monster in an H. P. Lovecraft book. The One-Not-to-Be-Named. The Magnum Innominandum. Humming songs and tunes we don’t know how to listen or dance to.

In cinematic creations that are now domiciled on any one of the streaming services that are familiar to us – Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime – there are many examples of these inhalatory moments when the intelligible melts away in the incandescent heat of a gasp. When one is in the presence of something so otherworldly that it takes the breath away.

Whether it is about artificial consciousness and robots in “Westworld” or about extra-terrestrial sentience in “The Expanse”[34], or the shocking inadequacy of human languages to accommodate the queerness of time in “Arrival”, the motif of our general incapacity to approach the otherworldly, to comprehend the messages that the planet may be streaming (partly) in the air; through our own bodies; through the presumptuous privacy of our ‘individual’ emotions; through the dog-eared tip of a browning leaf; through the belly-up swollen carcass of a whale that has ingested too many plastic products; and, through our many failures to address the ‘problem’[35] is the motif of this advent. And the ‘anticipatory assumption’ that we will fix climate change, that we can act as if we were in a prior world, blinds us to other energetic possibilities for living on a ‘damaged’ planet.

‘Where’ we are is so alien to us that we don’t know how to make sense of its thrashing limbs and bellowing groans. The terrestrial is (now become) extra-terrestrial. And the ground beneath our feet is unrecognizably – even jarringly – “other” that to walk upon it is (with every footfall) to be undone, and to enact close encounters of a seventh kind.[36]

***

“How do we organize within climate change in a way that does justice to its unboundedness, its unthinkability and its incalculability?” ask Campbell, McHugh and Ennis. What do we do here in this strange place? How do we mark failure or know success? Are the twain even to be considered apart as we once did when things were neat and tidy? What intelligences are peeking through otherworldly crevices, through yellow slit-eyes, blinking their curiosity, signalling wariness? How do we think when thought is frozen? How do we hope when hope is queered? How do we approach when movement and presence is called into question?

The beautiful and phantomatic word “Selah” appears a number of times between the Books of Psalms and Habakkuk of the Tanakh. 74 times. Its Hebraic etymology and grammatology is mysterious and its meaning is in doubt. The trouble with this word goes beyond errors associated with translating the Hebrew Bible into other languages, since ancient iterations of the text seemed to have had just as much trouble with making sense of it.

Something material about the word resists full articulation, full ownership, full capture, showing up only in traces, like a ghostly apparition at the edge of an innocent photo. Like the momentary flaring up of the night sky as a comet sneezes by, leaving whispers and wishes in its unearthly wake. Like virtual particles flashing up and ‘disappearing’ into the seething void. Like the “ogbanje” spirits of Igbo traditional systems in east Nigeria, children who were said to “come and go” (to be born and then die shortly after) with such ease that they often did not live long enough to be named by their grieving parents. Like ‘Oumuamua’[37], the flat cigar-shaped interstellar object in its extrasolar pilgrimage through our solar system – the only traversal we’ve detected so far – that sparked a conversation in 2017 and 2018 about its possible affiliations with alien civilizations.

19th century Reform movement Rabbi and Professor of Rabbinical Literature Emil G. Hirsch wrote about ‘Selah’, his writings littered with Greek texts potentially obfuscating to the modern reader:

That the real significance of this curious term (or combination of letters) was not known even by the ancient versions is evidenced by the variety of renderings given to it. The Septuagint, Symmachus, and Theodotion translate διάψαλμα [author’s note: Greek for diapsalma or ‘apart from psalm’]—a word as enigmatical in Greek as is “Selah” in Hebrew. The Hexapla simply transliterates σελ. Aquila, Jerome, and the Targum give it the value of “always” (Aquila, ἀεί; Jerome, “semper”; Targum, for the most part = “in secula” or = “semper”)… Jacob of Edessa, quoted by Bar Hebræus (on Ps. x. 1), notices that instead of διάψαλμα some copies present αεί=; and he explains this as, referring to the custom of the people of reciting a doxology at the end of paragraphs of the liturgical psalms. In five passages (see Field, Hexapla on Ps. xxxviii. [Hebr, xxxix.] 12) Aquila offers, according to the Hexaplar Syriac, =”song,” the ἀσμα by which, Origen reports Aquila to have replaced the διάψαλμα of the Septuagint. According to Hippolytus (De Lagarde, “Novæ Psalterii Græci Editionis Specimen” 10), the Greek term διάψαλμα signified a change in rhythm or melody at the places marked by the term, or a change in thought and theme.[38]

Selah’s contested identity and queer status as something ‘apart from psalms’ and yet somehow connected to them – an interior exteriority, if you will – does not make its meaning any clearer. Hirsch takes solace in this indeterminacy, noting however that among modern appraisals of the word there is agreement that “’Selah’ has no grammatical connection with the text.” It is outside the economy of meaning it is intimately associated with. Hirsch writes that the word is “either a liturgico-musical mark or a sign of another character with a bearing on the reading or the verbal form of the text.” Given that the context for its usage was musical, this mark or sign may have issued an imperative to a choir-master. “The meaning of this imperative is given as “Lift up,” equivalent to “loud” or “fortissimo,” a direction to the accompanying musicians to break in at the place marked with crash of cymbals and blare of trumpets, the orchestra playing an interlude while the singers’ voices were hushed. The effect, as far as the singer was concerned, was to mark a pause.”

Hirsch slowly identifies “Selah” with a pause, a mood swing, a falling away from the page. A reconsideration. A reframe. A thickening and loosening of threads. The erotic moment the weft penetrates the warp. The disposition of the Selah is to signal the moment of the traversal – something outside of the configuration and yet intimately entangled with the configuration. The advent. The otherworldly crosshatching the ‘this-worldly’.[39] Eternity bursting through the linear temporality we are mired in, opening up other opportunities and geometric performances of power-with. Selah marks the spot of silence. A hush as an angel whizzes by, leaving only an electrifying trace in the sky.

Thinking of climate change as Selah-ric enacts a pause, a slowness that is qualitatively deeper than a reduction of speed. This is a different kind of ‘slow’: the kind my own elders embraced when they said, with words much different than I can remember, “the times are urgent; let us slow down.” Selah invites us into different kinds of experimental relationships with a phenomenon that we are bodily entangled with, and yet cannot be fully read or held down in place. Because it is about shimmering crossings, about breakthroughs and interruptions (or “intra-ruptions”?), Selah is the theo-political imperative of rhythms with a posthumanist fluency beyond our ability to process. There’s a messianic quality to its appearing and disappearing.

Benjamin: The way isn’t forward, it’s awkward

Selah works as a device to frame Meillassouxian advents and the responsibilities/imperatives they instigate. In this case, the imperative of the pause. But this frame is too wide. It doesn’t tell us what we can pay attention to. It says approach with hesitation, but what to approach? Further insights into the nature of Selah and the advents it frames are possible when we read both concepts with Walter Benjamin’s idea of the messianic.

Though Walter Benjamin – German-Jewish thinker, historical materialist, cultural critic, born nearly fourscore years before the First World War, fascinated with photography and images, dead by morphine pill overdose as his escape from the Gestapo proved futile – may not have written specifically about the diapsalmata, the Selah, he did write about the injustice of history and the messianic ‘moment’ when another temporal realm bursts through the linear continuity of history, upending the tyrannical march of modern progress. Reading Benjamin – and those who are writing the dynamics of our time through his revolutionary texts – it becomes difficult to fail to notice how Selah, especially when seen together with the phenomenon of climate change, is about time. Or specifically, history as progress. And the imperative to end it.

Benjamin witnessed the rise of Hitler’s Nazi, and obviously had a lot to worry about. Though the shadow of the Third Reich loomed large over Europe, spitting fire and crashing the cymbals of war upon every notion that stood in the way of its realization, eventually driving Benjamin to take his own life in 1940, through his lifetime he was deeply concerned about a larger “war” – one which engulfed the forces of fascism and focused his keen attention on a ‘resolution’. This war was the war between the past and the present. When Benjamin sat with studying this war, he unearthed the hidden construction of social and material relations that instigated an oppression of the past and fetishization of the future – the very same relationships between humans and the world that are part of the climate collapse phenomenon today. His critique of progress emerged from a desire to offer a “total reconception of the way history is written and understood”[40]… a desire to wrench time from the unidirectional flow of history with the might of the messianic. Only with this effort could he address the oppressive forces at the heart of capitalist Europe – forces we still contend with today.

Arcades grew in popularity in Paris after 1822, demonstrating an architectural mastery over iron – and leading to “an unprecedented ability to display goods…”[41] Blending this mastery of elaborately constructed covered passageways with the capitalist urge for newer and newer things, Paris became for Benjamin a “dream world” or mythical fairyland lost in its addiction to its own fetishes. Agreeing with Marx, he noticed that social relations were being displaced into objects.[42] In time those objects took on a life of their own, becoming more and more fantastic in their distortion of the ‘primary’ relationships they once referred to. In other words, capitalist Europe had fallen into a commodity fetishism that was increasingly committed to consumption.

Today, in contemporary society, one might notice this commodity fetish in the exhausting tautology of social networks like Facebook, where communication becomes a discretized object in itself, taking on the hitherto inconceivable values and attributes of likes, emojis and tweets in ever fantastical dissociations from prior material needs of communication. The same might be true of pornography and the erotic fetishization of sexual desire – the possession of which denies the experience of possessing. Because of the drive for novelty and the deadening self-referentiality that results when we allow ourselves the luxury of variability while simultaneously stabilizing (objectifying/fetishizing) everything else, our social relations become deleterious and predatory. One may think further along with Benjamin and his alarm about the transformation of relationships into objects of fantasy by pointing to the ways that contemporary justice is fetishized, becoming increasingly subservient to class interests and the desire to wrest modern power away from an ‘enemy’.[43] Or the ways that climate disaster feeds back into our self-assurance of righteousness, and guilt becomes a narcissistic reinscription of human agency over nature.[44]

By focussing on the Parisian arcades as a crystal instance of European capitalist modernity and the hidden structure of time that fuels the feverish quest for commodity novelty and progress, Benjamin worked to reimagine the matter of history, no longer as the flow of progress, but as something different. He wanted to rehabilitate the past, not by seeking to recover it but by breaking it loose from its methodical decommissioning by the forces of progress. By de-fetishizing it. The answer to fascism, to oppression, to exploitation and totalitarian regimes, wasn’t going to be a new fetish, a new object down the line that maintained the phantasmagorical sleep in modernity’s fairyland of commodities, but an awakening from that dream-filled sleep. The dream is progress: the “illusion” of continuity, the tyranny of a single story or time mode, the promise of a future summit or telos where history is actualized, the hope that in the course of things we might create a progressive response to climate change; the awakening is a standstill. The montage. Selah. The lightening shock of rupture undoing the steady phantasm of rapture.

Benjamin really called for something revolutionary: a cessation of history in a “flash that excludes any predetermination and prohibits continuity in whatever follows”[45]. This is the reason why Barad notes that “Walter Benjamin was a philosopher of fragments and constellations. Discontinuity and juxtaposition played strongly in his works, over and against continuity and linear succession.”[46]

For Benjamin, (climate) justice isn’t something to come down the line, pinned to some future time, sincethe historical continuum itself – the unidirectional and ‘inevitable’ flow of time from past to present to future – is the injustice to address. Redemption for the oppressed past and from late capitalist fascist tendencies isn’t written into enacting ever more progressive values, or relying on the promises of the nation-state or Silicon Valley, its politicians, technocrats and their bureaucratic legislations and inventions to come. History itself is the problem – the linear trajectory that treats moments as infinitesimally thin slices of ‘Now’ stacked upon each other, rushing from the irredeemable past to the fleeting present to the elusive future. The colonial assemblage of industrialized minutes, synchronized seconds, neoliberal economic considerations, flattened telluric bodies, rushing trains, and migrating spirits that together produce, sustain, and centralize the dominant modern figure of “Man”.

Progress, the unfurling of a manicured red carpet over moss-tinged stones and through the dense forests of the more-than-human, worlds the world in ways that centralizes Man. It is the matter that is at stake here – the issue to address head on.

Barad writes that for Benjamin, “a critique of the notion of progress is a central theme… including a certain faith in progress among those on the Left who would invoke it in the fight against fascism. But for Benjamin, progress is powerless to act against the destructive force of fascism: ‘No unfolding historical development will overcome fascism, only a state of emergency that breaks with a certain faith in historical development.” As Benjamin says, ‘One reason why fascism has a chance is that in the name of progress its opponents treat it as a historical norm.’ If both fascism and protests against it function not according to some exceptional mode of operation, but through the usual way things get done, through ‘democratic’ elections and state-sanctioned forms of violence, then resistance to fascism requires a rupture of the continuum of history, the bringing about of a ‘real state of emergency’.”[47] For Benjamin, the Left and Right are the same idea.

The challenge of emancipation from oppression lies in rethinking time-as-progress. Progress comes with its own world. When “time” is performed as progress, what results is a linear causality of events and – as such – a sterilization of the ecstatic connections and dynamic relationships that breathe life into everything. Linear agency is a teleological highway that runs through a field of invisible others rendered as resources. Progress is the view from the architecture of permanence and human centrality. It looks at the wilds and gives it purpose – converting and distilling its wildness into figures and bits and usable data we can manage; it insists on universal meaning and instrumentality. In a more-than-human world, insisting on pervasive purpose is violence, not discovery. This is the violence of the state. The violence of activist justice as inclusion within the state and access to citizenry.

The ‘trick’ of redemption is the interruption of this temporality of progress. A “state of emergency”, meaning more than violence applied by humans on humans, but an energetic event that “blasts open” the corporeal logic of progress, allowing multiple other temporalities to stream through.

How did Benjamin reinvent history, or think about the disruption of the flow of history? He offered the image of a constellation, a “dialectical standstill”, about which Barad writes:

Constellations, like crystals, seem to be purely spatial arrangements, but Benjamin uses them in a temporal modality: In particular, if “standstill” indicates the arrest of time, the crystallization of history in that configuration indicates an array of times. How can we understand this? When we gaze up into the night sky and see specific spatial configurations of stars we call “constellations,” the stars are not all the same distance from us. Some stars are farther away than others. And since the speed of light is a constant, when we look at more distant objects we are looking deeper into the past. For example, when we look at our closest star, the sun, we are seeing the way it looked eight minutes ago—that is, we are watching in the present something that happened in the past. Staring at a constellation, we are witnessing multiple different pasts in the present, some more distant than others. Constellations are then images of a specific array of past events, a configuration of multiple temporalities, “a constellation in being.”[48]

Thinking of history as a sprinkling of radical discontinuities, as a constellational assemblage of multiple temporal modalities, as an explosion that blasts through the highway of the single timeline of progress – making the past seductively available to the present and the present to the past – is the offering of the image of the standstill Benjamin wrote about. This image is the emancipatory awakening flashing up obliquely to render out of joint the inexorable march of progress. This is the messianic, this showing up or making evident of other temporal modes. The fourth advent.

But not so fast. We shouldn’t be so much in a rush to enumerate advents, indexing them as if they could fall into a progressive sequence. In fact, the concept of the messianic that Barad demonstrates through her reading of Benjamin takes her to her comfort zone of quantum field theory. Here, she shows how every atom is actually the point at which infinities cross each other out. A self-touching perversity in quantum field theory shows that every ‘thing’, every bit of matter, is already an “enormous multitude”:

Each “individual” is made up of all possible histories of virtual intra-actions with all others; or rather, according to QFT, there is no such thing as a discrete individual with its own roster of properties. In fact, the “other”—the constitutively excluded—is always already within (but not fully enclosed by the self): the very notion of the “self” is a troubling of the interior/exterior distinction. Matter in the indeterminacy of its being un/does identity and unsettles the very foundations of non/being.

Barad affirms that the messianic, this flashing up of indeterminate temporalities, this radical discontinuous springing forth of advents, is built into the very structure of matter itself. Advents are thus not ‘events’ that happen once in a while; every moment is charged with an advent. Every moment is charged with messianic power. This thick and constellational “Now” is the politics of Selah, the imperative to hush in the presence of the (new) ordinary, to notice the messianic in collective practices that slow down the flow of progress.

For Benjamin-Barad, we need not “wait” for some future moment. Here, in the thick now, dwells revolutionary opportunities for redemption.

It is important to stress that Benjamin isn’t speaking of the Messiah of theological conception – not a human figure that steps in at the end of history, but messianic time, splinters and traces of the eternal that interrupt the passage of time and its conformism to the dictates of progress. This stepping in (like advents) happens within history: the trace flashes up in history, but it is not of history. It is outside the text, seeing the text in the very posthumanist way the aliens in the movie, Arrival, saw time – as a constellational image, as rhythms of transience, not the transcendent and monotonous fetishization of the next.

Could what we call climate change be read as a messianic arrest of happening in its resistance to neat conceptualization, in its colossal rejection of temporal succession, in its defiance of thinkability and referentiality, in its ability to manoeuvre away from resolution, and in its demand for unprecedented forms of organization? And is this Selah a messianic moment, an advent that hushes us up and brings everything to a standstill, while charged with an invitation for unprecedented forms of organizing? Could it offer a revolutionary chance to address the past? Could climate change be the Meillassouxian World in its rhythmic passing away, in its inhalation/exhalation, tearing down the apparatus of progress, mocking the figure of the propertied Man, streaming in from other temporalities we have relegated to the “pre-Holocene” (the Ice Age we conquered)?

Postactivism: Living with the Ruins, Learning to Die, Decorating Downfall (A Conclusion?)

The world is not about to end; we are already living with a different World. We are already in the midst of loss and downfall. Suddenly, 2030[49] is not the object of our keen interest. “2030” is a framework of progress, another gesture that insists on noticing climate change as a challenge or problem. But the advent of the messianic forces upon us other temporalities. We see not just “2030” (the year when the IPCC says we reach a milestone in our efforts to ‘defeat’ climate change) but the lingering years of 1945 (Hiroshima), 1619 (first African slaves brought to Virginia in America), 1622 (Indian massacres), 1836 (lynching of Francis McIntosh), 1692 (Salem witch trials) and 1919 (Jallianwala Bagh massacre).

In a World that exceeds thinkability, in a world we have no language for, one ‘fundamentally’ delinked from a prior due to the traversal flashing up of ‘nature’ in her flamboyant passing away, and one in which forward movement is now impossible, we need new forms of inquiry. We need new ways of making sense. We need new ways of listening.

Postactivism is the collective inquiry into the kinds of organizing, capacities, response-abilities, im/possibilities and desires we intra-act with in a strange World. Instigated by Selah, the call for creative foreclosure, postactivism is the kind of work that feels fitting in these messianic moments.

A climate morality now divides between those fighting hard for climate justice and those who are said to deny climate change even exists. The conversation is locked between these opposing sides. And every opinion that even slightly deviates from the centrality of carbon, from the drive for new climate legislation, from the efforts to educate people about carbon emissions, is said to be tantamount to climate denial.

However, justice itself is queered in this strange new circumstance. With the container of justice blasted open, a rhizomic abundance of response-abilities spill forth.

***

I have often thought of the trickster God of the Yoruba people and diasporic communities in the Americas, Èsù, and stories that are told about ‘him’ and his relations with history. First of all, he is said to be the Dark Man of the “Crossroads” – the point at which forward movement is queered. Where bodies meet other bodies in strange intra-actions, and become diffracted. Stories abound about how he travelled with the slaves from the old Slave Coast in the Middle Passage towards the New World. Because of the duplicitous nature of the trickster, and his role as an instigator of new kinds of bodies and worlds, I believe that Èsù not only travelled on the slave ships, but also guided them to African shores in the first place. The world ended for millions of African communities who lost their kin to the transatlantic slave trade. But for Èsù, an experimental apparatus was being stitched; he was making creolized bodies, disturbing the purity of identities and opening up other places of power. For Èsù, from a posthumanist perspective, the Middle Passage was a rite of passage. A passing away.

Rites of passage are ways of dying wisely. In ways that are often unnoticed, in modest gatherings that belie the weight of their considerations, in ‘small’ and barely perceptible ways, people are experimenting with dying. They are heeding the call to fail, to embrace loss and transience, to notice themselves within a web of life that does not privilege human bodies or the fetish of survivability.

What is this death?

It is a multi-levelled one – the loss of a civilization, the irreversible death of difference (biodiversity) and the ultimate limit of the human project. This is a difficult conclusion to make, but speculative realism is the ability to write the statement ‘the end of organization’ without inserting a sub-clause – what Meillassoux would call the ‘secret codicil’ of modernity – namely all the statements, practices and strategies that buoy up a secret belief that this civilization will last forever. It is a bleak perspective because current ecological conditions can only elicit such a mood. An unflinching look at this situation invariably leads to despondency. Human activities have had irreversible consequences. The majority of humans who have lived on Earth have not been responsible – there will be many unjust deaths.[50]

This bleak perspective is not anti-futural. As Campbell, McHugh and Ennis aver,

The space for optimism in this picture comes from the opportunities within the creative foreclosure of the old World. By this we mean organizing for the end of the World that is an escalated…commitment to divest justly – a preparing for an end without apocalypse. Accepting what has occurred will, we contend, be the first step toward to an organizing without hope – without hope that we can return to the World that has ended. Bleak optimism is therefore Janus-faced; one side finally acknowledges the unbounded, unthinkable, incalculable nature of this new reality, the other side, a chance to experiment with organizational forms of justice, ethics, politics and reason that are without precedent. The bleak optimist realizes this, and enacts the creative foreclosure…[51]

This death is not the version of anthropocentric imagination. In a world that is entangled and entangling, the severity of an absolute terminal point and a cessation of being seems to me a reinstatement of that old binary that prohibited the material world from being a place of vitality. What if our dying is a spreading out, a creolization of bodies, a sanctuary that reworks our exhausted boundaries? What if dying is making sanctuary?[52] And what if this apprehension of dying as a posthuman endeavour is the happiness Benjamin connects to the messianic?[53]

***

Powehi. Climate change. Monsters at the gate. Advents. Selah. Their guttural cries must be heeded. Something ancient asks us to give account for our centrality. To heed is to die. And therein lies our deepest hope for potentially wiser worlds.

THE END…

[1] Roy Scranton

[2] Judith Butler

[3] An interdisciplinary field that looks at how science is affected by politics, culture, society and how science produces its knowledges.

[4] Barad, K. M. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning.

[5] Van Oyen, Astrid (2018). Material Agency. In ‘The Encyclopedia of Archaeological Sciences.’ Edited by Sandra L. López Varela.